La condition humaine

The West Building (the one with -- I suppose one says -- "classical art", as opposed to the East Building, successfully to navigate which one needs to be able to identify what is "modern art" and what is "contemporary art") did not interest me much, and nor did I expect it to do, for reasons which I will attempt now to describe. Two of my wife's favourite pieces of art are van Gogh's Starry night and Monet's Waterlilies (charmingly, and repeatedly, called 'Waterlillies' on a print we picked up somewhere -- making one, or at least me, wonder if there's a market for misfit prints as there is for misprint stamps). The former has actually grown on me (although I still wouldn't call myself a fan of van Gogh's work), but the latter, as does most impressionism, leaves me cold. In fact, while I wandered through the seemingly endless halls of the West Building, I saw next to nothing which stirred my imagination (aside from a bizarre statue of Diana having her thigh licked by a limber-tongued dog 1

That, anyway, was (aside from a brief digression at the end) the West Building; now I would like to discuss the East Building, specifically the "contemporary art" exhibit, which (small though it was) captivated me; and, more specifically still, two paintings over which I lingered for a long time. Before I do that, I would like just briefly to mention, lest any one of my legion of readers (according to StatCounter, eight visits since 28 July, only two of them from me!) want to tell me more about them in the comments, three works which I enjoyed very much and which were new to me:

- Giacometti's Hands holding the void, as I have already mentioned, at which I stared for some time, entranced by the figure's hands and puzzled by its eyes;

- Weber's Interior of the fourth dimension, which was intriguing but which I didn't really understand; and

- Feininger's Zirchow VII, which flirted dangerously with sliding so far into the abstract that I didn't like it, but which, again, intrigued me -- mostly because it seemed to me from across the room to suggest a subway train in motion.

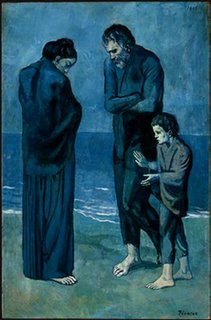

Now on to the two paintings of which I wished to speak in some detail. The first was Picasso's The tragedy:

As I have said, I am looking for a painting to surprise me, and, ashamed as I am of my pretentiousness, I can't make up my mind about this one until I know a bit more about it. It seems to me it could be either a rather mysterious painting -- wherein we are forced to wonder for ourselves what is the tragedy afflicting these three -- or a very mundane one. I will explain what I mean by the latter. If one believes that these three are looking at roughly the same thing -- it's a bit hard to tell, because, aside from the child, their eyes are lowered and half-shaded -- then it seems to be whatever the woman is holding in her arms, close to her chest. In thinking of what a woman might hold close to her chest, one thinks immediately of an infant; and it is not hard to imagine tragedies that might be connected to an infant. I do not, I think, belittle these tragedies when I say that to paint them is mundane -- in the sense, that is, that to do so depicts the world as it is, rather than as it might be. (This is another way to express what I look for in a painting, or indeed any art -- that it envision a world different from the one I know. I have planned a later post on literature in which I will elaborate on this point.) What I mean by calling myself pretentious is that, even though it is the same painting regardless of the artist's intent (or anyone else's interpretation), I find my enjoyment of it hinges on this question -- are we meant to understand in this painting some nameless tragedy, or some predictable and mundane one of the type I have mentioned?

As I have said, I am looking for a painting to surprise me, and, ashamed as I am of my pretentiousness, I can't make up my mind about this one until I know a bit more about it. It seems to me it could be either a rather mysterious painting -- wherein we are forced to wonder for ourselves what is the tragedy afflicting these three -- or a very mundane one. I will explain what I mean by the latter. If one believes that these three are looking at roughly the same thing -- it's a bit hard to tell, because, aside from the child, their eyes are lowered and half-shaded -- then it seems to be whatever the woman is holding in her arms, close to her chest. In thinking of what a woman might hold close to her chest, one thinks immediately of an infant; and it is not hard to imagine tragedies that might be connected to an infant. I do not, I think, belittle these tragedies when I say that to paint them is mundane -- in the sense, that is, that to do so depicts the world as it is, rather than as it might be. (This is another way to express what I look for in a painting, or indeed any art -- that it envision a world different from the one I know. I have planned a later post on literature in which I will elaborate on this point.) What I mean by calling myself pretentious is that, even though it is the same painting regardless of the artist's intent (or anyone else's interpretation), I find my enjoyment of it hinges on this question -- are we meant to understand in this painting some nameless tragedy, or some predictable and mundane one of the type I have mentioned?

This was the (relatively) lofty thought that first struck me as I looked at this painting. It was followed by a much more plebeian one, namely: "My God, that man's foot is hideous-looking!" (In fact, after a quick detour to find whatever naked feet I could in the gallery, I formulated the opinion that, despite centuries of evolution of art, people still aren't very good at painting feet.) After looking a bit closer, I realised that the problem goes deeper than that: Not only is one of the man's feet ugly and misshapen, the other one is at least half gone, disappearing after it goes behind the child's leg! This reminds me very much of a bit in A Far Side prehistory wherein Larson points out that, in one of his early cartoons, a man sitting at a table (in a courtroom, if I recall correctly) has a perfectly normal head and torso, but, curiously, no legs. The idea that Picasso ran into the same artistic trouble as a fledgling cartoonist cheered me very much.

The second painting was the one by Magritte to which the title of this entry subtly alludes. This was (to my disappointment, for he is by far my favourite artist) the only Magritte painting in the exhibit, and I almost passed over it -- for, as I have said, I look in a painting for some surprise; but I have by now seen this one, and its variants, so many times that they begin to seem (to my disappointment) almost banal. After I noticed the curious feet of the fellow in Picasso's painting, though, it occurred to me that this was an opportunity to see, up close, on a large scale, a painting which I had previously seen almost exclusively in scaled-down reproductions in books, and that I might as well take the opportunity to see if this different perspective offered anything new. I reproduce the picture below.

The interesting thing to me is that the canvas itself casts no shadow. Since the shadows of the legs are also unusually short, I'm not sure what to make of this, but it excites me to find something new in this familiar setting.

The interesting thing to me is that the canvas itself casts no shadow. Since the shadows of the legs are also unusually short, I'm not sure what to make of this, but it excites me to find something new in this familiar setting.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home