I have been trying for some time to find a good scan of

L'homme au journal, one member of the troika of my favourite Magritte works (the other members being the previously-discussed

La durée poignardée and

La reproduction interdite, on the second of which more below); but, unlike most other Magritte works (which have been relatively easy to find online), this one appears to be nowhere available -- at least, nowhere Google can find -- in good quality and at a reasonable size, so we will have to be content with the following image:

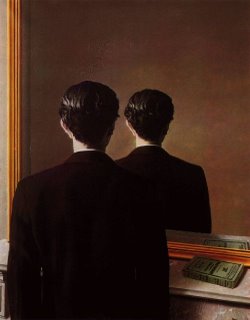

Perhaps predictably, it can also be somewhat difficult to find a good version of

La reproduction interdite, but here I think I have at least a reasonable one:

(Incidentally, while searching for this latter work, I found out that its subject is the surrealist poet Edward James, who -- one can only surmise -- was eager to model for Magritte but shy of having his face portrayed thereby; for he also is the subject of

Le principe du plaisir.)

I would like to discourse briefly on these two pieces. Actually, I have an opinion, the truth of which I am sure my meanderings to come will bear out, that there is little that can be said, by me anyway, about the impact or 'meaning' 1 of a painting or other visual work of art that cannot better be expressed simply by showing that work of art -- which is why I started my post in the way I did -- but you, my loyal and literate readers, do not stop by here to see pretty pictures, so I must justify this post with a few words at least.

I suppose I'll start with La reproduction interdite, both because (despite its exalted status in the top-rated triune) I like it slightly less (today, anyway) than the other, and because I have less to say about it. One obvious thing to wonder is: What is the significance of the book? In a larger print, it can be seen to be The adventures of Gordon Pym; but I do not know this story well enough to have any suspicion of whether there might be some message in the choice of it, or whether its position there is just happenstance. Well, I simply find this picture puzzling and intriguing, but apparently it panics some people: In All done with mirrors, Bevis Hillier is so frightened by the image that he (or possibly she) propounds an elaborate setup involving false walls and identical twins to forestall contemplation of the visual paradox.

Next we come to L'homme au journal. I have had some discussions with M (who does not find it particularly impressive) about why I like this work so much, but have never arrived at a really satisfactory explanation; so here's hoping that repeating the same inadequate words in the context of a blog will magically transform them into important profundities. I should start my discussion by pointing out that many Magritte paintings have English titles which are not literal translations of their French titles, and this one is no exception; its English title is Now you don't (as in, now you see it ...), which I find excessively showy. Indeed, the whole point of this work as I see it (and, indeed, it is surely obvious that I should be regarded as a greater authority on Magritte's work than some such nobody as, say, Magritte) is that one must not see the story it tells as one of great moment -- there is no magic trick being performed here for our benefit, no vanishing at which we should marvel open-mouthed; rather, what we are seeing is a mundane scene, of a man reading a newspaper, and, if the man should happen to vanish, it is just as plain and ordinary a happening (in the world this picture posits for us) as would be his remaining, placid and content. The universe -- this appears to me to be the central point -- goes on. I have resisted (though with some effort) the temptation to regard this work as a puzzle in the spirit of the ones I used to find in Highlights, in which one would be presented with two apparently identical scenes and asked to find the subtle points in which they differ, and so I do not know for certain that the last three panels are identical (to one another, and to the first panel with the offending subject deleted) -- indeed, as I discussed in my first post about Magritte, I have discovered that it is possible for me to find something new even in what seems to be the most familiar and unsurprising of his pieces -- but I hope very much that this is the case. To repeat myself, the point as I see it is the essential triviality of man -- though the gentlemen we see sits among contrivances (a chair, a table, a boiler) designed for and made to serve his convenience, when he is no more among them nothing changes. (I should mention a subtle point here which I admire, namely, the number of panels depicting each part of the narrative. It is important to the message of insignificance which I envision that the man be absent for more of the tale than he is present; if he were to be seen in two panels, and then not to be seen in two panels, there would be no message about the state to which the universe aspires -- so I believe; but perhaps, were the image otherwise, I would be moved to come up with a similarly ridiculous explanation for why it was so.) Somehow I find such messages in art, despite their essential bleakness, deeply comforting.

UPDATE 4 November 2006. I should have mentioned, in connexion with my previous post Tell your story well, but quickly, that another of my favourite stories was the last one in this group by Smedleyman.

1 This is a word which, in any artistic context, surely deserves

apologetic quotes; but nowhere should one be more apologetic about using it than when referring to Magritte, who (as I discovered at this

Magritte-inspired photo by Hogbard) explicitly discounted the idea of finding 'meaning' in his works, as follows:

My painting is visible images which conceal nothing; they evoke mystery and, indeed, when one sees one of my pictures, one asks oneself this simple question: "What does that mean"? It does not mean anything, because mystery means nothing either; it is unknowable.